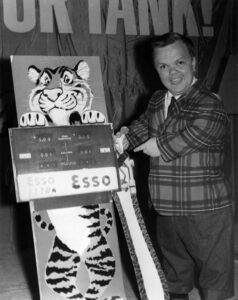

Dick Austin

July 13, 1932 – February 19, 1990

On February 19,1990, Richard (Dick) Austin passed away at K-W Hospital following complications from a prior stroke. A private family service was conducted at St. Louis Parish by our dear friend Father Bernie Hayes, who on short notice took time from his busy schedule. Soloist John Rodina and our family friend and organist Jim Donkers provided the music.

On February 19,1990, Richard (Dick) Austin passed away at K-W Hospital following complications from a prior stroke. A private family service was conducted at St. Louis Parish by our dear friend Father Bernie Hayes, who on short notice took time from his busy schedule. Soloist John Rodina and our family friend and organist Jim Donkers provided the music.

Predeceased by his parents Charles and Margaret Austin of Detroit.  Beloved husband of Mrs. Huguette Austin (Duhamel) and brother of Charles of Texas, Maryanne of Florida, Edward of Kansas, George of Michigan and Robert of Florida. Dear father and grandfather of son Donald and Rose (Zelinka) Austin, their children Christopher and Matthew; son Robert and Corinna (Holzamer) Austin, their children Sebina, Ian and Linsey; daughter Diane, her children Curtis and Nicholas; and son Tom.

Beloved husband of Mrs. Huguette Austin (Duhamel) and brother of Charles of Texas, Maryanne of Florida, Edward of Kansas, George of Michigan and Robert of Florida. Dear father and grandfather of son Donald and Rose (Zelinka) Austin, their children Christopher and Matthew; son Robert and Corinna (Holzamer) Austin, their children Sebina, Ian and Linsey; daughter Diane, her children Curtis and Nicholas; and son Tom.

We would like at this time to extend our deepest gratitude to Dr. Kent Bauman and the nursing staff of K-W Hospital for all their support, understanding and comfort. Our sincere thanks goes to all our many friends, relatives and organizations who comforted us in the recent passing of our dear husband, father and grandfather through thought, prayer and acknowledgements. We would also like to express our thanks to the children’s employers for their compassionate time off and acknowledgements of sympathy.

I LIVE IN A WORLD OF GIANTS – Richard Thomas Austin

MacLean’s Magazine – April 1, 1952

Nineteen years old and only four feet tall, Dick Austin still manages to drive a car and hold down a man-sized job. Here, he tells the lively story of a man living amid a race of behemoths — some of whom are his girl friends.

D ogs may be dogs to you but to me a large dog is as furious as a charging bull, as dangerous as a hungry lion and as fearful as a hippopotamus. You see, when I pull in my belt and deliberately draw myself up to full height, I am still only forty-eight inches tall. To me, a yardstick is a fair-sized hunk of timber. When I started growing, someone said WHEN! much too soon. As a result, a seven-year-old youngster literally looks down at me, while you are probably a giant when standing beside me.

ogs may be dogs to you but to me a large dog is as furious as a charging bull, as dangerous as a hungry lion and as fearful as a hippopotamus. You see, when I pull in my belt and deliberately draw myself up to full height, I am still only forty-eight inches tall. To me, a yardstick is a fair-sized hunk of timber. When I started growing, someone said WHEN! much too soon. As a result, a seven-year-old youngster literally looks down at me, while you are probably a giant when standing beside me.

I am what is known as an achondroplastic dwarf. I have a normal head and body but very short arms and legs, caused by a cartilage defect in the growth of my “long bones” or limbs. My arms and legs as a result are only about half the length they should be.

Science has yet to discover the reason for this condition. Dwarfs are born (often stillborn) once in about six thousand births. The condition is definitely not hereditary and can happen irregularly in anyone’s family tree.

My parents are both normal. I have four brothers and one sister all of better than average height, all chips off the old block.

I am nineteen years old, successfully supporting myself. I board out, clothe myself and manage to save a little each week. I work as an announcer at a radio station, CKCR in Kitchener, Ont. Waking up our listeners and sending them off to work each morning in a happy mood is a real effort. I am often only half awake myself. I love my work and am accumulating experience in every phase of radio operation.

But about those dogs. If a large dog rushes in your direction with a vicious hungry look in its eye, you can easily plant a size nine boot under its chops. I have a dainty size three and a half. The best I can do is kick it in the knee and hope it dies laughing. Usually the dog is merely infuriated. You can protect yourself with your arm. Mine’s so short, I’m afraid it might accidently slip down the dog’s throat and be nipped off at the armpit. In a real crisis, you can run away. My fifteen-inch legs, even when in a hurry, shatter no records.

Not everything in my diminutive world is quite as fearful as large dogs. In the main I get along as well as the next fellow. I’ve lived an astonishingly normal life as far as it has gone. I ask no special favors and seldom get any. Certainly there are limitations, inconveniences, aggravations and irritations but I meet them as they come.

My day usually begins with a feud between me and a bedroom dresser or a chest of drawers. Somewhere on the top is my tie clip—I need it. If there is a chair or stool handy it is easy to retrieve it. Otherwise I have to use ingenuity. I am forced to pull the drawers out part way and use them as a ladder.

My next port of call in the morning is the bathroom. The mirror is usually located midway between the floor and ceiling. My hair is a mess, how can I see to comb it? I scramble up the washstand and into the washbasin. I sit on the edge and leisurely separate the curls from the whirls.

The guy that invented hall trees misnamed them. I can climb a real tree but those things are impossible. When I’m alone I’ve tried tilting them to slip my coat off the hook. Often the clothes tree and I end up on the floor.

Things I do find awkward are some restaurant stools. You have merely to place your posterior near one of them and collapse. I have literally to mount the things. Some of the higher ones are next to impossible. Water fountains can be equally difficult. If I have a friend with me I ask for a boost. If I’m alone, I go thirsty. Stairs aren’t too easy for me. High bus steps are miserable. Walking through deep snow is a struggle. Puddles are a menace passing cars give me a heel-to-head bath.

Tall people give me a pain in the neck. Not because I dislike them but only because when we are both standing I have to tilt my head back to converse.

Hasty people have called me an independent little cuss. For that I say, “Thank you.” It’s exactly how I want to be. I’ve met other short people who have led pampered lives. I’d much rather make my own way. For that I thank my mother and my family. When the doctor realized I was going to be the exception in an otherwise normal family he instructed my mother, “Whatever you do, show him no favoritism—for his own good. He’s going to have tough going when he butts up against the world. Don’t further handicap him by making him dependent upon you or the others in the family.” She heeded his advice.

Stools or steps were always placed conveniently around our house. If I wanted anything off a shelf I used a stool and got it myself. If I wanted a drink of water or had to wash my hands I climbed steps. Nothing was cut down to my size. I got along in a household of giants as best I could. I was just another member of the family. If my brothers got into mischief, I was in the thick of it with them. If they lined up for a spanking, I was in the line-up and took the same punishment in the same general location.

I have been told I’m cocky for my size. Maybe I am. I’d much rather strut like a bantam rooster than slip away like a timid quivering quail. People might look over me but I don’t let them overlook me.

I received a little extra attention at school. They built up the seat so the teacher would know if I was present. That was when I was five. I think I was about twelve when I fully realized that the other fellow’s would always tower above me. I’d grown my last inch then. My pals had another twenty inches to go. At twelve I also left home to attend boarding school because my parents thought it would help me. I have never been home since, except during holidays. I’ve attended schools in Detroit (where I was born), Simsbury, Conn., Montreal and Kitchener, and what an education I’ve had!

To most people, getting along with the other fellow is one of the ABCs of living. To me it is the whole alphabet. When you’re my size, it’s not only good sportsmanship to be sociable and agreeable, it’s good common sense. With arms too short to fight and with legs too short to run away, I’ve had to learn to take a joke.

All the odds aren’t against me. Baseball, for instance, is my favorite game and I can hold my own on any sandlot. I’m a hard guy to pitch to and have sent more than one pitcher to the benches suffering the jitters. The speed I lose on base running is compensated by the number of times I’m walked.

I get a great kick out of basketball. It’s fun playing against a new team. They’re trained to guard and check regular-sized players. When they see me dribbling the ball down the gym they’re afraid I might run between their legs.

They forget rules. They start swatting my head instead of the ball. If they see I’m going through unchecked, they’ll actually grab at me like a fellow after a slippery minnow. In desperation they sometimes hit me with a rugby tackle, bowling me over until there is a heap on the floor. My teammates like that. They look for a penalty—I look for bruises.

Half Price At The Movies

My friends sometimes say, “Boy! are you lucky. You can buy and wear kid’s clothes.” That’s where they’re wrong. I weigh one hundred pounds even but I wear man-sized clothes. The trunk of my body is of normal size. It’s just my arms and legs that are short. That’s how I differ from a midget. A midget is a dwarf who is tiny all over. When I buy a suit I buy a man’s suit. The legs have to be cut down to fifteen inches, the arms to twelve inches. I buy a size fourteen shirt and cut the sleeves down. Most people are lucky to have enough material left over for a patch or two. I have enough material over to patch the whole suit and enough after that to patch the patches. But no one mistakes my clothes for theirs. The other students at school were continually losing, loaning, borrowing, swiping and exchanging clothes with other students. I had no such difficulties— that is, if you don’t count ties. I wear standard neckties.

I guess I’ve tried most of the things a “nineteener” has tried. I have been sneaky enough to take advantage of half fares on local buses. When the driver glances at me I point to the mark on the measuring post. It actually worked several times. Then I bumped into a driver completely devoid of humor. “The rest of the rule says,” he sneered loudly, “if the CHILD is accompanied by his mother. Either produce your mother or pay full fare.” I quietly slipped another coin in the box and took a seat.

Half fares have worked at movies, but not often. The best chance is to get my ticket quickly before the cashier has an opportunity to think, or is still too surprised to argue. But there is also the ticket taker to beat. When I’m with a girl friend I pay up like a man.

High wickets at banks, movies or post offices can make me feel insignificant. I’ve stood close to the wicket and asked the clerk for, say—a ticket. He looks about, dully thinking he heard someone. When his eyes prove him wrong, he simply makes a mental note about ghosts and goes back to his immediate occupation of staring into space. In such situations I’ve almost yelled myself hoarse. Now I back up—farther and farther so that I again become visible, in line with his vision, over the top of the counter. I’ll éven wave my arms if necessary to attract attention. When I have his eye I again advance toward the wicket and make my request as he sheepishly leans over the counter toward me. Similarly, in a noisy room or location, I’ve often found a tug on a guy’s trousers saves time, temper and tongue.

Yes, I have girl friends—as many as the next teen ager. And I like them in the same sizes and assortments. I like a pretty face and properly placed curves—is that normal? I go to dances all the time and like to dance. Unfortunately there are frequently girls who are embarrassed by my size. In those cases, the first date is the last.

A Patter For The Platters

And then there are mothers! Some put their foot down and refuse to let their daughters go with me. It is rather disconcerting to feel you are listed in the same category as an undisciplined, disreputable or undesirable character. I don’t even drink or smoke. Someday, perhaps, I’ll settle down with the one and only, and there’ll be children—normal ones—my doctor assures me the odds are greatly in our favor. Even mated dwarfs can expect to have normal children.

One summer, when home on vacation, I managed to get on a radio quiz program on WWJ, Detroit. In two minutes I’d won a portable radio. Two days later one of the station’s directors phoned me and asked if I would be intei’ested in taking a position with WWJ. He said my voice had broadcasting possibilities. I accepted but my parents vetoed the idea. “First,” they said, “education. Then a job.” I went back to Montreal rather deflated.

Months later at St. Jerome’s College, Kitchener, a thought struck me. I was very keen on jazz records. “Why,” I thought, “couldn’t I write a patter about different band leaders with sidelights on orchestras and records? Perhaps I could wangle a part-time job at the local 250 watter, CKCR.”

keen on jazz records. “Why,” I thought, “couldn’t I write a patter about different band leaders with sidelights on orchestras and records? Perhaps I could wangle a part-time job at the local 250 watter, CKCR.”

When I had about two weeks programs arranged, I went to the station and talked with Gib Liddle, the manager. I remember looking up at him and expecting he’d break out laughing. He took his time checking the list. I was wondering if he’d notice if I quietly slipped away. I could have jumped on his knees and patted his head when he said, “Okay. Let’s try it.” I worked part time until the school term ended, then went on a full eight-hour schedule. A good salary and pleasant conditions have made me a very thankful fellow.

Youngsters, from five years to about eight, never cease to amaze me. Their frankness is often disconcerting. No matter how prepared one is, they blurt out the unexpected. If puzzled, they stand and stare. Kids around that age are about the same height as myself. I have had kids stand with their noses almost touching mine stare in complete bewilderment. They don’t know how to classify me. They know I’m not the same as themselves but aren’t quite able to reason it through. It happens frequently: A mother will be walking along holding her son’s hand. She will stop to look into a store window or perhaps to wait for a traffic light. Her youngster spots me and stares. Then he’ll strain to get a little closer. The mother will eventually wonder why the youngster is pulling away from her -—look to see what’s the matter—and often be horrified at the predicament her youngster has gotten her into. She’ll give him a jerk that nearly tosses him off his feet and scold and shake him as she hurriedly tries to put distance between us. The mother of course is terribly embarrassed. The youngster is hurt and scolded, all because he saw something he didn’t quite understand and was doing his best to reason it through. Now, when I see a kid staring at me, I start talking to him. Ask him his name— where he’s been, anything to take his mind off the situation and save the inevitable round of embarrassment.

A woman at one of the lunchrooms I patronize often sits at the table with me and we have a little gab fest. Her energetic five-and-a-half-year-old son rushed into the restaurant to tell her the latest school news. She said. “Ray, this is Dick Austin. Shake hands with Dick.” Ray stretched out his hand, looked at me intently and then back at his mother. For the lack of something better to say, his mother explained, “Dick works at the radio station.” That threw Ray for a loop, he looked at me incredulously and scoffed,“Works at the radio station? He isn’t old enough!”

“How old do you think I am, Ray?” I asked.

“Oh!” with studied consideration, “Oh! I guess maybe six or seven or maybe eight.”

“I’m nineteen, Ray.”

He looked over at his mother, smiling slightly, expecting the joke to pop at any minute.

“That’s right Ray, Dick’s nineteen.”

Ray looked back at me, searched every inch of me from head to foot. Looked me squarely in the eye and spluttered, “Wow! Pretty darn tiny aren’t you?”

I’ve scared the pants of! many youngsters by telling them I’m small because I smoked too early. Whether this one-man campaign will seriously affect the tobacco industry remains tó be seen.

One of my pleasures that is also a financial pleasure is professional tap dancing. I’d sooner tap than eat.

When A Little Man Dreams

The favorite routine with Merv Himes’ band in Kitchener is to have me carried  on the stage in a bull fiddle case or a music trunk. The gag consists of blowing smoke out through an opening and then, after the whole band has gathered around with fire extinguishers, mops and water pails, out I jump, smoking a large stogie and start tapping. Merv has a favorite trick of increasing the tempo until it is impossible to keep up with the beat. Routine is thrown overboard. I glide, jump, slide, pivot, twirl—anything to keep up the pretense of dancing. Every kick, every movement is original and so l keep going until either myself or the band collapses from exhaustion. You don’t have to tell the audience what happened, they’re tied up laughing. If I had my way I’d get mad but I’m too short of wind. By the time I get my wind it’s too late.

on the stage in a bull fiddle case or a music trunk. The gag consists of blowing smoke out through an opening and then, after the whole band has gathered around with fire extinguishers, mops and water pails, out I jump, smoking a large stogie and start tapping. Merv has a favorite trick of increasing the tempo until it is impossible to keep up with the beat. Routine is thrown overboard. I glide, jump, slide, pivot, twirl—anything to keep up the pretense of dancing. Every kick, every movement is original and so l keep going until either myself or the band collapses from exhaustion. You don’t have to tell the audience what happened, they’re tied up laughing. If I had my way I’d get mad but I’m too short of wind. By the time I get my wind it’s too late.

A woman cornered me at a social one afternoon. Between sips of tea she told me she was an amateur psychologist. “I am very interested to know, she explained, “what a little fellow like yourself dreams about. Tell me: in your dreams, do you imagine yourself to be a large, dark, handsome man, say six feet tall? Or do you dream of yourself as being actually smaller than you are?” Before I could answer she was away again. “Perhaps in your dreams you remain exactly the size you are? I’d be terribly interested to know. Of course if you don’t wish to tell me, or if I’ve offended—.”

“I’m awfully sorry, lady,” I finally managed to squeeze in, “but my dreams are so far apart I can’t even remember when I had the last one. In fact, I can’t even remember any dream I’ve ever had—they’re so seldom.”

“How utterly disappointing,” she cooed. “I wonder, would you mind informing me if you do have a dream sometime soon? Or better yet, a nightmare?”

“I’ll try to do better than that,” I promised. “Some night just before going to bed I’ll eat three huge Limburger sandwiches. That should force something.”

During my final term at St. Jerome’s, I filled in as a spare teacher whenever necessary. When I stretched to full height I could only write about two lines along the bottom of the blackboard. I had no choice except to stand on a chair. The students were amused. But I got even with them. I also took two forms of outdoor PT exercises. When I had them lined up I showed no mercy. I reasoned if I could do the exercises, so could they. If I could do twenty or more push-ups they could too. I kept them hopping until I was almost ready to drop. Since those days I’ve had time to consider—whom was I actually punishing?

When people get to know me, one of their eventual questions is “Don’t you wish you were normal size?” As my pals phrase it, “Don’t you long to be longer?” or “Don’t you aspire to be higher?” My honest answer is a definite NO. If there was an operation or method of shooting me up a couple of feet I think I’d refuse. I’m completely oriented to my way of life. Who wants to be average? Why do women wear those funny little hats? Why do men wear loud ties? Isn’t it an effort to make themselves different—to get out of the average class? Yes, I’ll stay the way I am. I can do anything you can do—well, almost anything. Everything I do is a challenge. There is little opportunity for monotony. I own and drive a car—a Fiat with extensions on brake, clutch and gas pedals. I can also swim, skate, play competitive games (you should see me at ping pong), golf (with regulation clubs), bowl, and do a thousand and one things. I’m convinced I’ll get much more enjoyment doing the ordinary than you will. To me, everything new I try is an adventure. Surely it’s better to be short than tall.

Take the repair man checking radio lines at our station recently. He was six feet eight inches tall. We had a field day comparing sizes. We laughed at each other’s difficulties. I think he envied me. He was forever hitting his head on beams, doorways and arches.

We compared boot sizes, arm lengths, shirt sizes. Everything he wore had to be made to measure. Everything had an extra charge tacked onto it. He almost wept when I explained how much stretching room I had in bed.

He traveled the country sleeping at hotels. He always went to bed with a “hang-over”—two feet hanging over the end of his bed. I told him how much fun I had in bathtubs, how I could even float. He couldn’t remember ever having had room to straighten his legs. Even a shower was a source of danger. If he closed his eyes he might bang his face against the spray nozzle.

“You even have the advantage over me peeking through keyholes,” he chuckled.

“Sure,” I replied, “but consider the advantage you have peering over transoms.”